“Neuro-” refers to the brain

The word “neuro-” comes before the word “development”. This is mainly referring to the brain.

The brain is a mass of nerves. Neurodevelopmental disorders are disorders caused by the development of the brain. Therefore, it is important to note that it refers to disorders in the childhood, just like physical growth. In other words, the brain develops just as the body does, so any disability that arises at that time may become less severe or more noticeable as the child grows up to an adult.

A typical case of a symptom that becomes less noticeable as the brain grows is the hyperactivity symptom of ADHD.

Hyperactivity peaks in the early elementary school years, but many children improve considerably in the upper grades. On the other hand, the “inattentiveness” symptom of ADHD often becomes more noticeable in adulthood, not as the brain grows, but rather as the speed of social development exceeds that of the child, and the child’s symptoms come into focus. This is called the “outer gap” (between you and the society), which is one of the relative gaps that I referred before.

The term inattentiveness is used to describe a state of inattention, which, in addition to just inattentive, strongly implies “absent-mindedness and lack of participation”. This type of inattentive ADHD is colloquially referred to as the “Nobita type” as opposed to the hyperactive “Gian type,” which is likened to Doraemon. Unlike the Gian type, the Nobita type is not particularly noticeable in elementary school, so they often grow up without being noticed by parents and teachers, regardless of their grades. However, as soon as they become “adults” and are required to live independently, they tend to have episodes that affect their social life, such as “not listening to others” or “not remembering appointments,” and are often noticed by others with complaints.

The term “neurodevelopmental disorders in adulthood” refers to the secondary distress after owning ASD/ADHD features. In this case, the depression, anxiety and other mental symptoms pronounced by ASD/ADHD are the major focus.

Disorder is a condition that is not in order

“Order” refers to a situation in which you are part of the average majority and are in balance and control. For example, the phrase “Everything is in order.” can be used to mean that everything is “going well under control”. Disorder is a state of being far from this order-ness.

As you may have noticed, disorder is included both too poor AND too much, meaning hypo- and hyperdevelopment of the structure of the brain.

So, what do we compare the degree of brain development to, in the end, is the average (=ordinary) brain structure of the majority.

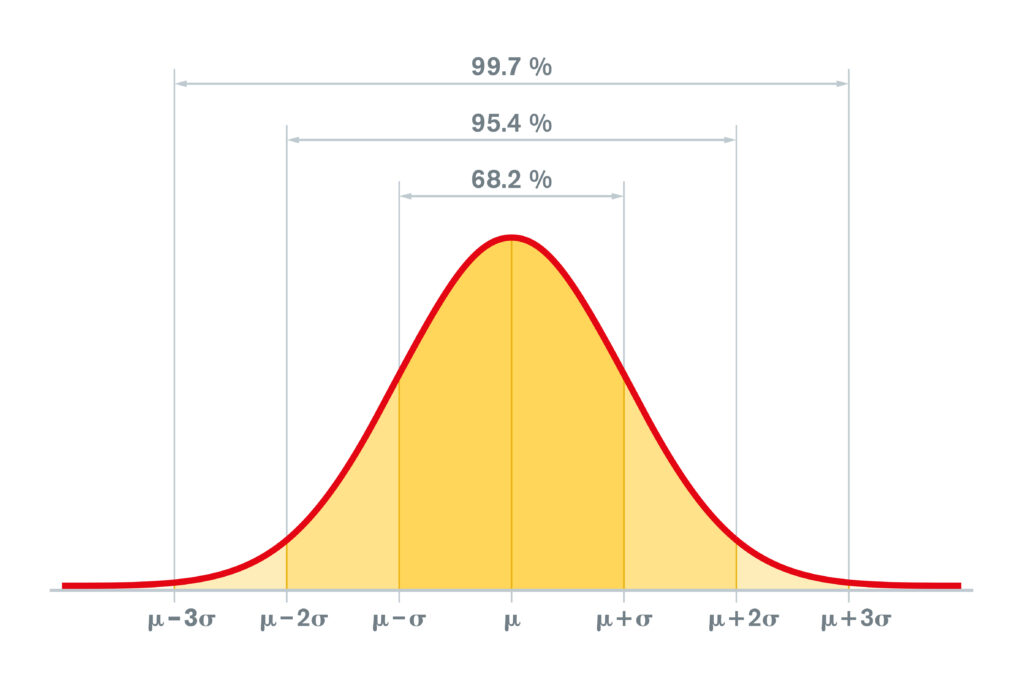

If you have studied mathematics, you may have seen the “normal distribution” of the bell curve as shown in the above figure.

For example, in the case of children’s height, weight, and head circumference, which is called the growth curve, the “order” is the group that contains about 95% of the children of the same generation. The top 2.5% AND the bottom 2.5%, or a total of 5%, are defined as disorder.

Statistical disorder is usually defined as the total of these 5%. In the figure above, this corresponds to the lightest orange area to the left of μ-2σ and to the right of μ+2σ.

Children for neurodevelopment, adults for secondary symptoms.

Neurodevelopment, on the other hand, is not so simple as physical growth.

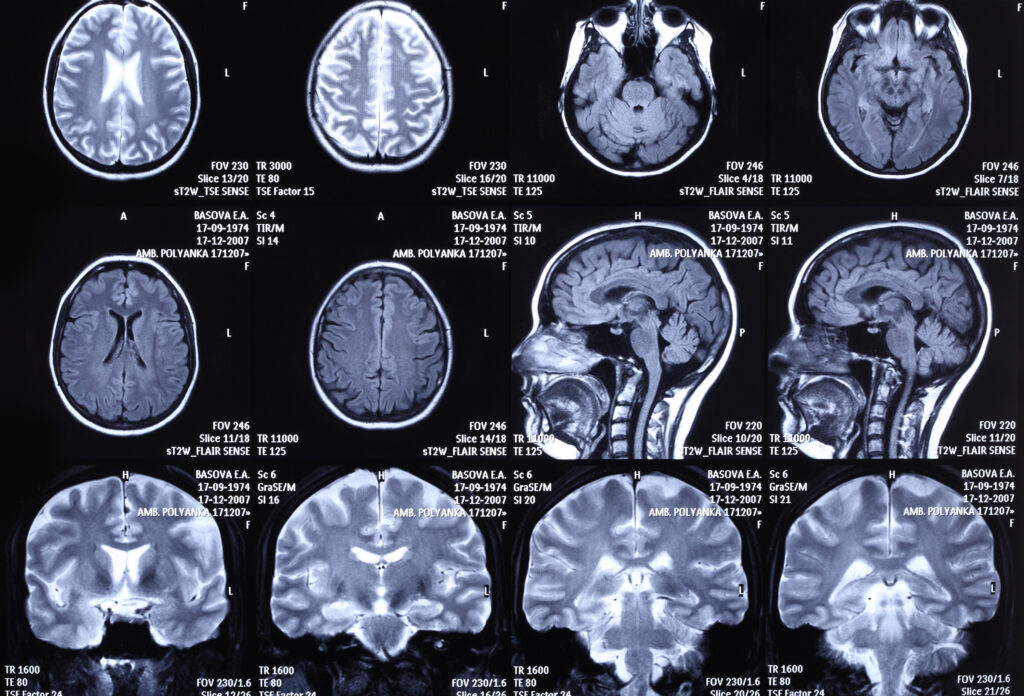

First of all, unlike group physical check-ups at schools, not all people of the same generation have their brains medically-imaged by MRI, so we have to use imaging data from a limited group.

Secondly, even if the structure of the brain is clarified in detail, it is impossible to diagnose a disease based on that alone. For example, even if it is found that ADHD is characterized by a relative overdevelopment of the “X” region of the brain, the degree of development does not correspond to the degree of symptoms of ADHD. This is where “relativity” or relative gaps come into play to a great extent, and is the reason why diagnosis is so difficult.

The third reason is that the diagnostic criteria for each of the disorders included in the neurodevelopmental disorders themselves do not directly refer to the mal-/overdevelopment of the brain structure, but rather to the extent to which that structure affects the behavior and social adaptability of the individual.

In particular, if your first-time visit to a mental clinic for neurodevelopmental disorders is in adulthood, we would have to focus on evaluating the mental symptoms such as depression and anxiety. Because the development of the brain is already completed in adulthood, it is more important to focus on making everyday-life easier than “labeling” ASD/ADHD. As an indication of this, there is an increasing number of over-the-top cases where a person is simply having difficulty adapting at work, but is told by his or her boss that he or she has an “ADHD” or an “ASD” and should go to a clinic. Of course, this is just an excuse or a synonym for the boss’s desire to have the work go smoothly.

The psychiatrist doctor will listen to the family’s related episodes about the patient’s childhood, referring the teachers’ comments, performance/grades at school, and the records at birth and neonatal/infantile growth and development, etc., and listen to the consistent episodes of disability and distress since childhood. The diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorders cannot be made until these pieces of information and episodes are put together in one coherent string of distress.

Beyond the diagnosis, there is treatment, and the goal of treatment is to prevent the degradation of self-efficacy due to repeated “failure stories” and “difficulty in living” from childhood that originate from the person’s traits. By preventing this decline in self-esteem, the goal is to help the patient to be able to manage life secured even after becoming independent as an adult.

Difficulties in living as a child may be perceived as stress beyond the imagination of adults. This is because there is a large relative gap between his/her internal and external performance. This gap between input and output skills of the individual is what I call the “inner gap”. (Note that it is a different relative gap from the outer gap mentioned above.)

For those who have already reached adulthood, we focus on the secondary psychiatric symptoms such as depression and anxiety caused by such low self-esteem and self-evaluation. Since there is already “difficulty in living” from childhood on the first floor, anxiety and depression on the second floor, no matter when they are created, have the tendency to persist and worsen. It is the mission of mental health clinics not only to provide such treatment, but also to prevent the worsening or appearance of symptoms.

Consistent distress is significant

Returning to the topic of diagnosis, for example, if we consider a situation that interferes with one’s daily life as a “dot,” such as always missing the deadline for submitting documents at work, it is actually not possible to make a diagnosis unless there are two or more “dots” of situations.

The point is that it is necessary to verify whether or not some kind of distress is occurring not only at the workplace, as in the example above, but also at home, for example. In the workplace alone, it is not possible to understand whether it is simply a matter of compatibility with the work environment or your own traits.

Your traits will remain the same no matter where you are or what you are doing, but your environment will change from time to time, interacting with you in ways that may be negative or positive.

The important thing to remember at this point is that the starting point is not your boss or family, but whether you yourself have been consistently feeling troubled throughout your life.

It is essential to make a decision that excludes such “interests” as much as possible. This is why the judgment of a professional third person is so important.

>The double suffering —The relative gaps between the outer and the inner: To Be Continued